Five-Year HIV Screening Policy Campaign Proved to Save Lives

April 30, 2025

HIV screening rates for MAP and MAP Basic patients in Travis County were found at rates 64% higher than the state average and 84% greater than the national average.

AUSTIN, Texas—For thousands of people, a positive HIV diagnosis used to feel like a death sentence, especially during the peak of the AIDS epidemic in 1995. And it was a sobering truth, with more than a half million AIDS-related deaths reported.

But in 2025, that reality has shifted, with easily accessible and lifesaving treatment options available. People who are HIV-positive can have full lives. They can talk openly with health care providers. Today, a person with HIV can manage the condition properly with the right care.

Still, that doesn’t mean prevention doesn’t remain a major issue.

Life-threatening gaps continue to exist. And a big part of the problem is due to screening.

A Policy Change

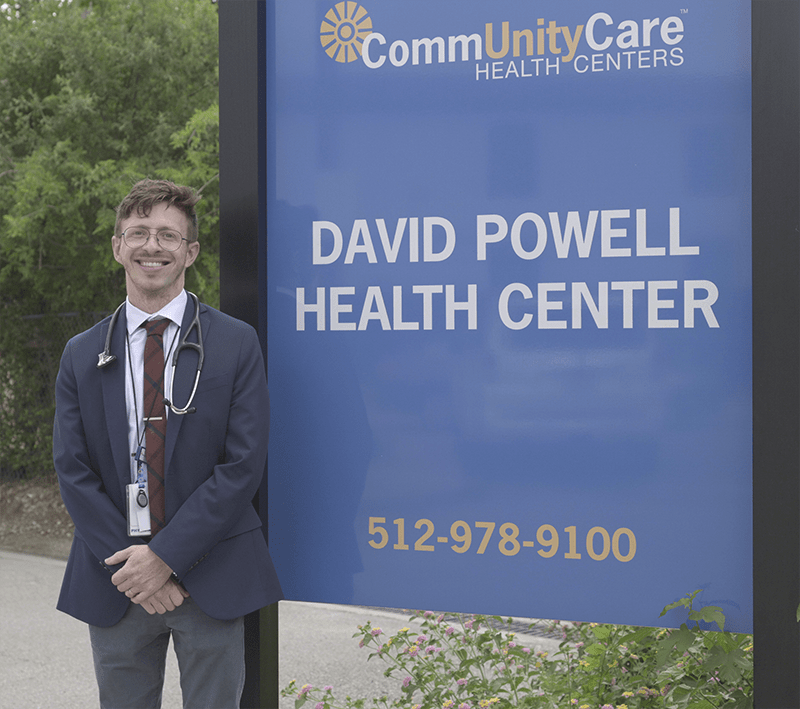

For over 30 years, the David Powell Health Center has provided HIV treatment to a 10-county range in Texas, including Travis County, where the CommUnityCare clinic resides and where Central Health serves its patient population.

The David Powell Health Center long ago created a policy to include HIV as part of any blood screening, leaning on the recommendation of the Centers for Disease Control, which urges hospitals and clinics to test all patients from ages 13 to 64 for HIV.

But for a long time in Central Texas, and in health care facilities across the county, patients were slipping through the cracks. Illnesses and conditions weren’t being properly identified until it was too late.

Cases of HIV were advancing to AIDS. Patients were dying.

In 2018, Central Health’s Policy Council (CHEP) wanted to ensure Central Health was taking the right steps to reduce those health outcomes. The group developed and implemented a five-year HIV screening policy campaign adopted by five health care systems over a period ending in 2023, including CommUnityCare Health Centers, People’s Community Clinic, Lone Star Circle of Care, El Buen Samaritano, and St. David’s South Austin Medical Center.

The goal was to detect HIV at the earliest possible stage and to connect positive patients to wrap-around medical care as soon as possible. When it was implemented in over 50 clinical sites in Central Texas across those systems, the policy secured a wide-ranging impact.

“Research shows that requesting an HIV screen can be a barrier,” said Megan Cermak, senior director of public health strategy at Central Health and a member of the Policy Council. “It also shows inconsistencies among who providers talk to about risk factors and getting screened. An opt-out screening policy levels the playing field, reduces stigma and barriers, and makes screening a routine part of healthcare.”

The Policy Council—formed in 2015 and led by a coalition of over 80 community representatives in “Shark Tank”-like policy reforms—leaned on the ability of Central Health as a payor of medical services to contract with community health organizations and build-out guidelines.

The campaign, which sought to diagnose gap areas in testing in Travis County, adopted CommUnityCare’s policy model, mandating an HIV screening on blood tests unless patients opted out.

The results were lifesaving.

After five years of reporting data across clinics, Central Health learned that enrolled members in its Medical Access Program (MAP) and MAP Basic, two health care coverage options for Travis County residents with low income, were screened for HIV at rates 64% higher than the Texas average and more than 84% greater than the national average in 2023. The numbers didn’t lie–Travis County was Texas’ epicenter for HIV infections.

What’s more, a study by the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at The University to Texas at Austin found that HIV opt-out screening accounted for just $2.61 in additional costs per patient but added 28 quality-adjusted years of life per patient and diagnosed 1.25 new infections per 7,000 new patients over a given year.

“These statistics aren’t just numbers. They represent our friends, relatives, colleagues, and neighbors whose future depends on timely, dignified care that gives them a chance to live longer and healthier lives,” said Central Health President & CEO Dr. Patrick Lee. “This campaign is proof that when we normalize HIV screening and make it more accessible, we can prevent premature deaths and make a meaningful impact. We’re committed to building on this momentum as we continue advancing our mission of improving the health of our community by caring for those who need us most.”

A study by AIDSVu, a data-charting resource maintained by Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health, found that 21 new HIV cases per 100,000 residents in Austin were reported in 2022, which was eight cases above the national average. Austin’s prevalence rate for HIV was also 90 cases higher than the national average.

“What the (HIV Screening) campaign encouraged was for anyone entering one of these health care systems, that they would get the same standard of care,” said Dr. Michael Stefanowicz, director of intensive outpatient clinics at the David Powell Health Center. “We aligned with what the standard of care for HIV screening should be. We included it for anyone who may otherwise qualify without exceptionalizing the HIV test. It was a way to encourage people to screen for HIV and normalize the conversation.”

Standard of care continues to be top of mind on Capitol Hill, too. Recently, Texas state Representative Venton Jones (D) authored House Bill 50, which sought to normalize HIV testing as part of regular STD screenings. It earned unanimous approval in the Texas House before it fell in the Senate.

Lifesaving Data

The efficacy of the Policy Council campaign had a direct effect on Travis County residents. Patients diagnosed with HIV were immediately connected to medical providers, found effective treatments to manage viral loads, reduced transmission, and ultimately increased lifespans.

“The whole purpose behind the initiative was this idea that the earlier we can diagnose, the earlier we can link patients to care,” said Brandon Wollerson, a member of Central Health’s Policy Council who pitched the HIV screening policy on World AIDS Day on December 1, 2017. Wollerson is now senior director of philanthropy & community engagement at Vivent Health, an HIV-prevention organization.

“Once people are on medication and in care, they will not transmit to partners. That’s what science tells us now. It’s U=U.”

U=U is a slogan used in HIV/AIDS education to reduce the stigma of the condition, inform the larger population, and reduce barriers to care.

With just over 5,400 people currently living with HIV in Austin, according to the 2022 study by AIDSVu, health outcomes continue to improve. But there remains a small subset of the population living in the dark, with over 1,000 HIV cases—accounting for 17% of the HIV-positive population in Austin— still reportedly undiagnosed in the city.

In Travis County, statistics surrounding HIV diagnoses show that the disease has no bias toward gender or ethnicity. While men occupy most cases (87.3%), a small but significant percentage of women (12.7%) are also living with the disease. Across racial lines, HIV impacts white (32.8%), Latino or Hispanic (38.8%) and African American (22%) communities nearly equally.

“The goal has always been to eliminate health disparities,” Wollerson said.

Overcoming Stigma

The city of Austin became a “fast-track city” in 2019, meaning it joined a global partnership of 380 cities to work toward ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

But stigmas around HIV still exist, Dr. Stefanowicz said.

The CommUnityCare physician learned that many years ago as a social worker in Philadelphia, where he helped unhoused people on the streets with advanced needs for care.

“One of my first clients as a social worker in Philadelphia was a man who had advanced HIV,” said Dr. Stefanowicz, who says this moment and many more prompted his leap into medicine. “He was very sick. And this was before medical management was easier than it is today. He died from medical complications. So that moment taught me how housing and social determinants of health can have a profound impact on health outcomes, especially in those living with HIV.”

Ultimately, several facets of the HIV screening campaign were vital to its long-term success, including HIV education and buy-in from those five Travis County health care clinics and systems. But perhaps the most important factor was reducing barriers to care – eliminating the stigma of asking for an HIV screening in the first place. By including it with any blood test, the campaign immediately created positive health outcomes.

“What this is saying to our patients is that sexual health is an important part of overall health,” Dr. Stefanowicz said. “We need to not stigmatize it. We need to not exceptionalize it. HIV screening should be as routine as any other test.”

Five years after the HIV screen campaign, of the original participants continue to issue opt-out HIV screening policies and report data back to Central Health.

Wollerson, who remains a part of the Policy Council, says the next ideation of the HIV screening policy should include buy-in from medical hospitals and emergency rooms in Travis County.

“As programs in sexual health face potential cuts (at the national and local level), that shifts some burden on to the community,” he said. “HIV isn’t going away. It still will be in Travis County, so it begs the question: If our organizations end up having to make difficult decisions, emergency rooms and hospitals will have to play an even more important role in this fight.”